At the end of November, DC Comics released Doomsday Clock #1, the first in a twelve part sequel to Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ legendary superhero deconstruction Watchmen. Doomsday Clock writer Geoff Johns, aided by artists Gary Frank and Brad Anderson, feature in their story not only Watchmen characters Ozymandias and Rorschach, but also two figures unconnected to the 1985 original: Superman and Lois Lane, the first of many popular DC heroes slated to appear in the series.

Doomsday Clock is the culmination of Johns’s year-long project enfolding the Watchmen characters into the mainstream DC Comics Universe. Or, more accurately, enfolding mainstream DC characters into the Watchmen universe. Various stories by Johns, beginning with 2016’s DC Universe: Rebirth #1, have revealed the company’s line-wide reboot—which largely erased the characters’ past histories so their stories can begin anew—to be the result of meddling by Watchmen’s godlike Doctor Manhattan.

On a plot level, these stories find Batman, Flash, and others fighting to defend decency against Manhattan’s machinations. On a metatextual level, they pin the blame on Watchmen for the comics industry’s turn from away from optimistic do-gooders toward gritty anti-heroes such as Wolverine, Lobo, and Deadpool.

I find this move doubly disingenuous. It ignores both Alan Moore’s super-hero reconstructions, like 1963 or Tom Strong, and Geoff Johns’s own tendencies to mix sex and violence into his stories. And worse, the move subscribes to an intensely shallow reading of Watchmen.

Without question, Moore and Gibbons make superheroes look pretty bad. Their characters fight crime not because of their devotion to good over evil, but because of mental illness, self-delusion, and outright sadism. Daniel Dreiberg (aka Nite Owl) and Laurie Juspeczyk (aka Silk Spectre), the book’s most morally upright figures, suffer from literal and metaphorical impotence, while violent nihilists the Comedian (aka Eddie Blake) and Rorschach get most of the attention from creators and readers alike. The book’s overall plot concerns the world’s smartest man, Adrian Veidt (aka Ozymandias), thwarting World War III by faking an alien invasion, driving heretofore warring nations to join together against this manufactured threat, but killing millions of innocent New Yorkers in the process.

Despite these elements, the book is not nearly as cynical as its reputation suggests. It gives full attention to the selfish motivations of those with power (super or otherwise), but ultimately discards them as fundamentally weak or unsustainable.

Take the realpolitik driving Veidt’s master plan. As indicated by the book’s lone hero shot—Veidt raising both fists in the air and shouting “I did it!” after learning that nuclear nations have turned away from the brink of conflict—Watchmen does suggest that only a common enemy brings people together. However, Moore and Gibbons undercut Veidt’s conviction by ending his story with a conversation with Doctor Manhattan. When Veidt asks, “I did the right thing, didn’t I? It all worked out in the end,” Manhattan merely observes “In the end? Nothing ends, Adrian. Nothing ever ends” and disappears, leaving Veidt alone with his empty glass globe and his looming shadow.

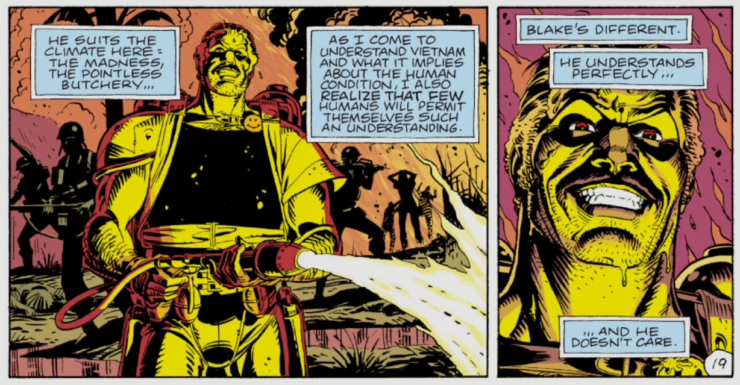

Likewise, Eddie Blake, whose murder initiates the plot, spends most of the series justifying his cruel behavior as a type of realism: the futility of life in an age of nuclear weapons renders everything meaningless. “Once you figure out what a joke everything is, being the Comedian’s the only thing that makes sense” he tells Doctor Manhattan, who describes Blake as someone who “understands perfectly … and doesn’t care.” Gibbons accompanies Manhattan’s narration with a close-up of Blake’s face, grinning as he torches as Vietnamese village.

Blake’s visage appears at other points in the book, in very different contexts. One of the more striking instances closes Blake’s drunken rant at the apartment of retired supervillain Moloch, to whom Blake has turned after learning of Veidt’s alien invasion plans. In place of nihilistic bravado—the conviction that meaninglessness awarded him a license for cruelty—Blake’s face now indicates utter powerlessness. “I mean, what’s so funny,” he asks Moloch; “What’s so goddamed funny […] Somebody explain it to me.”

Nearly all of the cynical worldviews represented in the book play out in the same way: established, then explored, but ultimately revealed as untenable. Rorschach adheres to the most objective black and white binary between right and wrong and proclaims, “Not even in the face of Armageddon, never compromise,” but wears on his face the most subjective of psychological tests. Likewise, Doctor Manhattan dispassionately pronounces that individual human lives are insignificant, but constantly broods over the events of his own life, before and after his nuclear-powered apotheosis.

No matter how much the characters of Watchmen adhere to a morality that devalues human life, they all find themselves deeply affected by and clinging to other people.

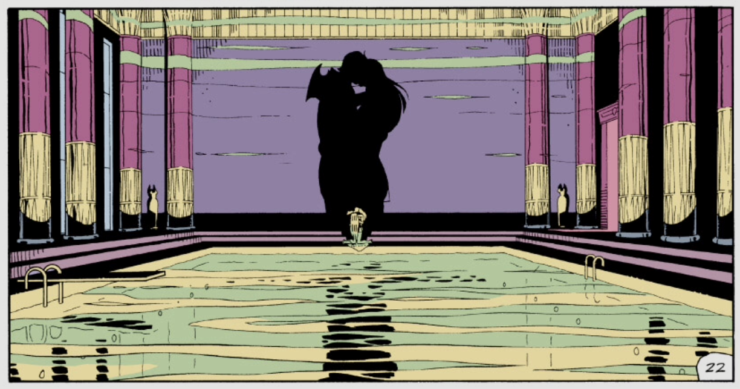

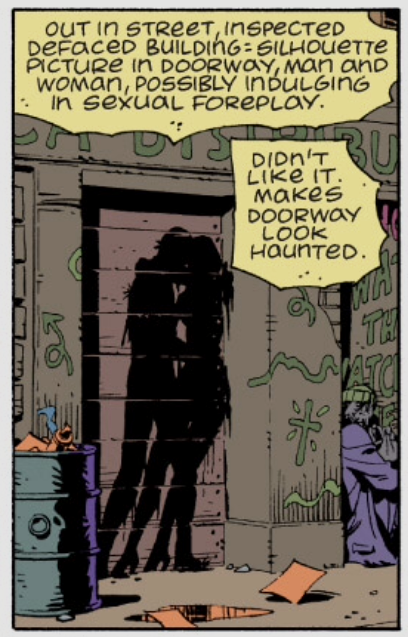

This humanist ethos is revealed in the story’s most prominent reoccurring image: two people embracing, often in silhouette. It regularly appears as graffiti decorating the city, pictures that Rorschach claims make the spaces look haunted. The observation becomes personal when the blotches on his mask take that form, and again when he recalls seeing on the wall the shadows of his prostitute mother and one of her johns. These shadows reveal Rorschach’s certitude to be not moral conviction, but a response to his mother’s abandonment—not a disengaged ethics but a longing for connection.

Rorschach’s psychiatrist compares the graffiti to “people disintegrated at Hiroshima, leaving only their indelible shadows on the wall,” foreshadowing Moore and Gibbons’s most striking use of the image: at the epicenter of Veidt’s attack, an old newspaper seller embraces a young man reading comics at his booth, the two holding one another against the annihilating blast.

The embrace comes at the end of a series of interactions between the two—the older man named Bernard, the younger Bernie—sprinkled throughout the book’s twelve chapters. Initially, Bernard extols the virtues of selfishness. “In this world, you shouldn’t rely on help from anybody,” he tells his young visitor; “In the end, a man stands alone. All alone. Inna final analysis.”

Bernard prides himself on his unique ability to divine wisdom from newspaper reports, and while he never loses his penchant for bloviating at visitors, his compassionate side emerges as nuclear war becomes increasingly inevitable. After reading a headline about Russian hostilities in Afghanistan, Bernard offers Bernie a comic book and the hat from his head. “I mean we all gotta look out for each other, don’t we?” he says, revising his position: “I mean, life’s too short … inna final analysis.” And when he finally faces the end, Bernard does not—as he originally claimed—stand alone, but reaches out to comfort a man with whom he shared nothing but proximity and a name.

Nearly all of Watchmen’s minor characters have similar realizations and, not accidentally, they all converge upon Bernard’s paper stand at the moment of the alien invasion. The trials of Joey the Cabby and her timid girlfriend, or of psychiatrist Malcolm Long and his estranged wife, or of beleaguered detectives Fine and Bourquin may get lost among the superhero melodrama in the book’s main plot, but Veidt’s explosion transforms their tales into high drama. The blast might engulf the people and their stories, but it also reveals their struggles with one another to be the stuff of imminence, the substance of lives lived together in the shadow of the unthinkable.

This realization drives Moore and Gibbons’s inversion of Watchmen’s most iconic image: the bloody smiley face. For the Comedian, the smiley face represents his belief that nothing matters and existence is a joke; Blake’s blood splattered across it testified to Veidt’s conviction that individual suffering matters not at all in the face of the greater good.

But the smiley face appears again in a different form, at the end of chapter nine, which features Laurie Juspeczyk’s conversation with her ex-boyfriend Doctor Manhattan. Manhattan teleports Laurie to Mars, where he is living in exile after growing disinterested in earth. Worried about nuclear war and vaguely aware of Veidt’s plan, Juspeczyk begs Manhattan to intervene and prevent humanity’s extinction, making desperate appeals he callously dismisses. Against the suffering and cruelty of human life, Manhattan shows Laurie the intricacies of Mars’s beautiful, lifeless terrain and asks, “Would it be greatly improved by an oil pipeline?”

Moore and Gibbons seem sympathetic to Manhattan’s position, intercutting the philosophical Martian wanderings with scenes from Laurie’s own unpleasant life—her fatherless childhood, her mother’s contentious relationship with Eddie Blake. The two threads come together when Juspeczyk realizes that Blake is her father, a revelation that drives her to destroy Manhattan’s glass palace and to fall on her knees in Mars’s red dust.

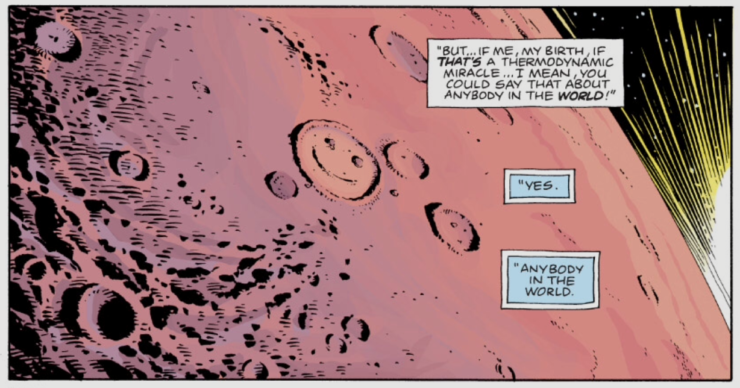

Upon recognizing that she is the Comedian’s daughter, Juspeczyk temporarily adopts her father’s worldview. “My whole life’s a joke. One big stupid, meaningless…”, she starts to say, but is interrupted by Manhattan, who counters, “I don’t think your life’s meaningless.” Continuing his scientific approach, Manhattan describes human coupling as a thermodynamic miracle: “events with odds against so astronomical they’re effectively impossible, like oxygen spontaneously becoming gold.” Out of all the possibilities, one of a thousand sperm happened to impregnate a particular egg after one out of a billion men coupled with one out of a billion women—two people who, in this case, despised one another—to make the person who became Laurie Juspeczyk. The tiny and insignificant is the miraculous, according to Manhattan. “Come… dry your eyes, for you are life, rarer than a quark and unpredictable beyond the dreams of Heisenberg; the clay in which the forces that shape all things leave their fingerprints most clearly,” he rhapsodizes.

Manhattan’s revelation here repudiates all the other characters’ philosophies, particularly the Comedian’s. As Manhattan gives his monologue, Gibbons pulls back his “camera” more and more in each frame, not only rendering minuscule the characters on the planet’s surface, but also revealing geographic features that take the shape of a smiley face. Oblivion does not render individual lives meaningless, this reversal suggests; rather, the threat of oblivion makes individual life cosmically important.

This is the same realization Bernard has when he reaches for Bernie in the face of the annihilating blast, the same realization represented by the graffiti that haunts the book. That’s why the image occurs one last time, when the death toll of Veidt’s plan overwhelms Juspeczyk and she tells Dreiberg, “I want you to love me because we’re not dead.” The threat of destruction forces the couple to face the precarious preciousness of life, a point Moore and Gibbons make in a panel showing their entangled shadow amplified on the wall.

This emphasis on empathy and connection should be just as much a part of Watchmen’s legacy as its deconstruction of heroic tropes and assumptions. The writers of Doomsday Clock are not wrong address the cynical aspects of the original story, nor the deleterious effect its imitators have had on the genre. But when searching for hopeful aspects to restore to superhero stories, they need not look further than Watchmen itself—a tale of care and understanding.

Joe George‘s writing has appeared at Think Christian, FilmInquiry, and is collected at joewriteswords.com. He hosts the web series Renewed Mind Movie Talk and tweets nonsense from @jageorgeii.